Interpersonal Functioning in Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

Originally published by: Journal of Personality Assessment

Written by: Nicole Cain, PhD, Emily Ansell, PhD, H. Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, & Anthony Pinto, PhD

The core symptoms of obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) often lead to interpersonal difficulties. However, little research has explored interpersonal functioning in OCPD. This study examined interpersonal problems, interpersonal sensitivities, empathy, and systemizing, the drive to analyze and derive underlying rules for systems, in a sample of 25 OCPD individuals, 25 individuals with comorbid OCPD and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), and 25 healthy controls. We found that OCPD individuals reported hostile-dominant interpersonal problems and sensitivities with warm-dominant behavior by others, whereas OCPD+OCD individuals reported submissive interpersonal problems and sensitivities with warm-submissive behavior by others. Individuals with OCPD, with and without OCD, reported less empathic perspective taking relative to healthy controls. Finally, we found that OCPD males reported a higher drive to analyze and derive rules for systems than OCPD females. Overall, results suggest that there are interpersonal deficits associated with OCPD and the clinical implications of these deficits are discussed.

Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is characterized as a chronic maladaptive pattern of excessive perfectionism, preoccupation with orderliness and detail, and need for control over one’s environment that leads to significant distress or impairment. Prevalence of OCPD in outpatient settings is estimated between 8% and 9% (Zimmerman, Rothschild, & Chelminski, 2005) and in the general population between 2% and 8% (Grant, Mooney, & Kushner, 2012). Individuals with OCPD find it difficult to relax, feel obligated to plan out their activities to the minute, and find unstructured time intolerable. In addition, they are often characterized as rigid and controlling (Pinto, Eisen, Mancebo, & Rasmussen, 2008). This need for interpersonal control in OCPD can lead to hostility and occasional explosive outbursts of anger at home and work (Villemarette-Pittman, Stanford, Greve, Houston, & Mathias, 2004). Despite the negative interpersonal consequences associated with OCPD, little research to date has systematically examined interpersonal functioning in this clinical population. This study aimed to examine how individuals with OCPD view themselves and others, using established measures of interpersonal functioning, empathy, and the drive to analyze and derive underlying rules for predicting and controlling interpersonal interactions.

One method for examining interpersonal functioning in OCPD is to use the interpersonal circumplex (IPC; Leary, 1957). The IPC is rooted in interpersonal theory, which posits one’s interpersonal style can be described using two orthogonal dimensions: dominance and warmth.

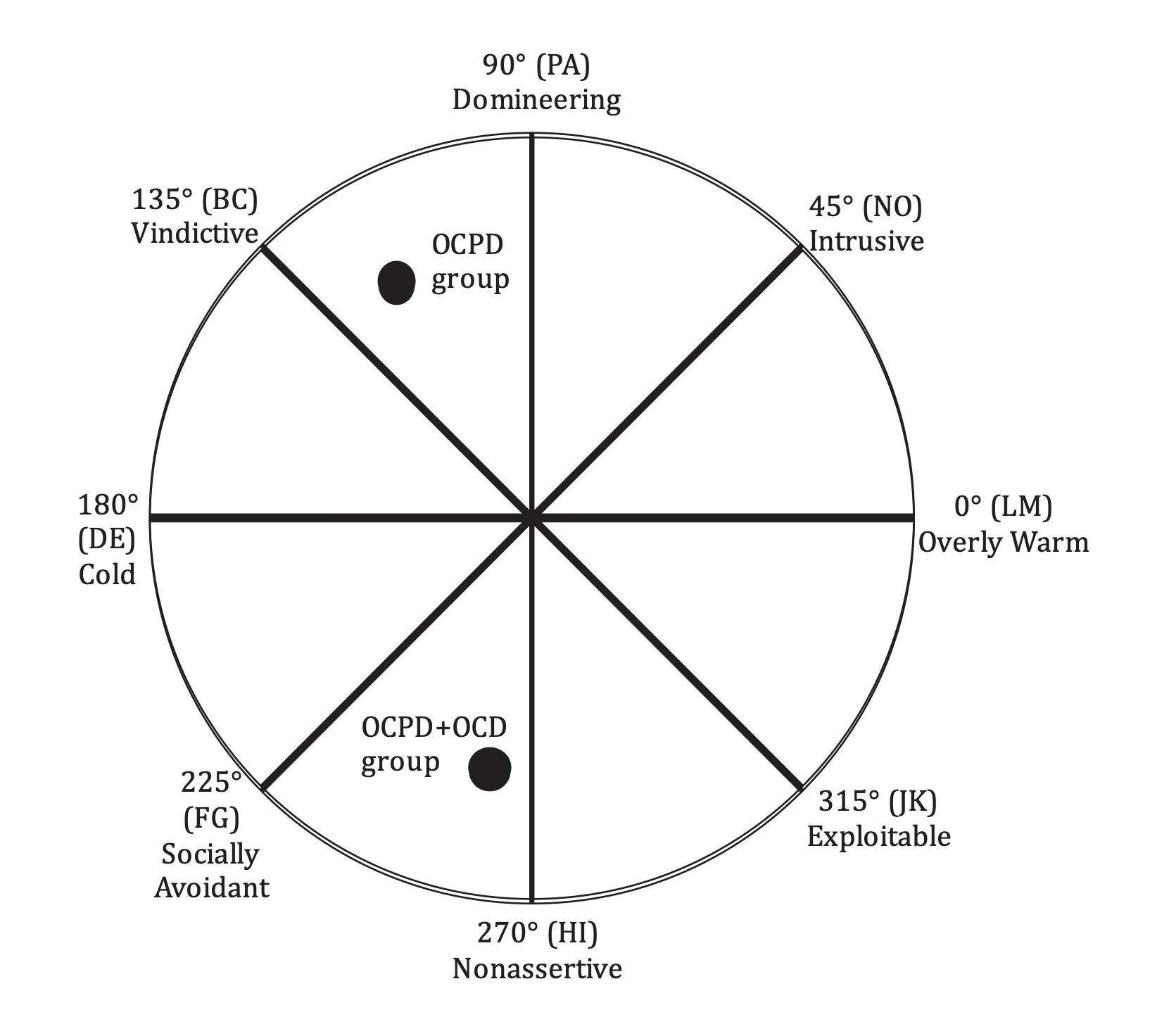

This model depicts an individual’s interpersonal style by placing him or her in the two-dimensional space created by the orthogonal dimensions (see Figure 1 for an example of the IPC; Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 1990). Circumplex octants offer useful summary descriptors of interpersonal behavior, marking the poles of the main dimensions but also representing blends of the underlying dimensions (i.e., hostile-dominance or friendly-submissiveness; Pincus & Gurtman, 2006).

Previous research using the IPC to investigate interpersonal functioning in OCPD has yielded mixed results. For example, using the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems–Circumplex (IIP–C; Alden et al., 1990), Pincus and Wiggins (1990) reported that OCPD, assessed using the Personality Adjectives Checklist (PACL; Strack, 1987), was not associated with a predominant interpersonal style in a nonclinical undergraduate sample. In contrast, Soldz, Budman, Demby, and Merry (1993) found that OCPD, assessed using the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–II (MCMI–II; Millon, 1987), was related to nonassertive interpersonal problems in a clinical sample of personality-disordered patients referred for group psychotherapy. Matano and Locke (1995) also found that OCPD, as assessed by the MCMI–I (Millon, 1983), was associated with nonassertive interpersonal problems in a heterogeneous clinical sample of patients in a drug and alcohol treatment facility. However, in a more recent investigation relating OCPD to the IPC, Cain (2011) found that the overall construct of OCPD, assessed using a multidimensional self-report measure, was associated with hostile-dominant interpersonal problems and high interpersonal distress in a large online sample partly recruited from websites and organizations that specifically target individuals with OCPD. One explanation for these mixed findings could be the different types of samples and assessment methods used in each study. To date, no study has examined interpersonal functioning in a clinical population with a principal diagnosis of OCPD.

FIGURE 1. - An example of the interpersonal circumplex and circumplex locations of the obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and OCPD + obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) groups.

Note. The eight octants found in the interpersonal circumplex (Interpersonal Problems Circumplex; Alden et al., 1990). Octants are labeled with the alphabetical notation originally provided by Leary (1957; e.g., PA, BC, DE, etc.). OCPD group (n = 25) located at 121.54° with an amplitude value of 0.78, and OCPD+OCD group (n = 25) located at 261.78° with an amplitude value of 0.58. All angular locations are approximate. The distance from the center of the circle indicates vector length, or an index of profile differentiation (e.g., closer to the center of the circle indicates lower profile differentiation, farther from the center indicates higher profile differentiation).

The IPC could also be used to investigate the interpersonal sensitivities associated with OCPD. Henderson and Horowitz (2006) argued that others’ interpersonal behaviors are irritating to individuals because they frustrate interpersonal motives (Horowitz et al., 2006). For example, individuals who tend to value independence, autonomy, and social distance would be expected to be the most frustrated by those who are clingy and dependent, whereas individuals who value assertiveness would be the most frustrated by passivity in others. This framework suggests that people might be differentially sensitive to specific forms of aversive interpersonal behavior by others because their interpersonal motives vary along the dimensions of dominance and warmth (Henderson & Horowitz, 2006).

Hopwood et al. (2011) investigated the kinds of aversive interpersonal behaviors that are likely to be most bothersome for a person with a given interpersonal style and found that individuals tend to be bothered by interpersonal behavior that is opposite to their own behavior. For example, individuals who are warm and loving were most bothered by others who were cold and withdrawn. They also found that in a sample of undergraduate students, individuals reporting high antisocial personality traits were most bothered by warm, submissive interpersonal behavior, whereas individuals reporting high dependency traits were most bothered by cold, dominant interpersonal behavior in others. The specific interpersonal sensitivities associated with OCPD have not yet been explored.

Another method for exploring interpersonal functioning in OCPD is to examine the systemizing mechanism (SM) and capacity for empathy. Baron-Cohen (2006) described SM as a way of understanding and predicting the law-governed inanimate world. It is the drive to analyze the variables in a system, to derive the underlying rules that govern the system, to predict the behavior of the system, and finally to control the system. Systemizing allows the brain to predict that event X will likely occur with probability P. Baron-Cohen, Richler, Bisarya, Gurunathan, and Wheelwright (2003) reported that males spontaneously systemize to a greater extent than females. In contrast, empathizing is a more fluid way of understanding and predicting the social world. It is the drive to identify another person’s emotions and thoughts and to respond with the appropriate emotion (Baron-Cohen, 2006). Previous research has shown that women spontaneously empathize to a greater extent than males (Wakabayashi et al., 2006).

Hummelen, Wilberg, Pederen, and Sigmund (2008) suggested that the core pathology of OCPD includes perfectionism and its associations with rigidity and aggression that lead to difficulties in interactions with others. The authors concluded that these core features of OCPD might be related to the systemizing mechanism and argued that OCPD individuals are high on systemizing and low on empathizing. Hummelen et al. argued that OCPD develops out of an inborn tendency toward systemizing, which leads to more rigidity, stubbornness, and perfectionism than average. For example, if an individual with OCPD experiences a significant other as unpredictable or not following the “rules,” then he or she might experience frustration, irritability, or even rage. The conclusions of Hummelen et al. based on the systemizing mechanism could offer one possible explanation for the link between OCPD and interpersonal hostility noted in previous research (Cain, 2011; Villemarette-Pittman et al., 2004). However, to date, no study has examined the link among systemizing, empathy, and OCPD.

Finally, one of the difficulties in investigating interpersonal functioning in OCPD is its high comorbidity with obsessive– compulsive disorder (OCD). Prevalence data support a relationship between these disorders, with elevated rates of OCPD (45.0%–47.3%) in individuals diagnosed with OCD (Gordon, Salkovskis, Oldfield, & Carter, 2013; Starcevic et al., 2013). Recent research on OCD using the IPC suggests that OCD exhibits interpersonal heterogeneity, with OCD individuals reporting exploitable, nonassertive, and intrusive interpersonal problems (Przeworski & Cain, 2012). The high rates of comorbidity between OCPD and OCD as well as the interpersonal heterogeneity associated with OCD might offer another possible explanation for the contradictory findings in previous research using the IPC to investigate interpersonal functioning in OCPD. Previous studies (Matano & Locke, 1995; Pincus & Wiggins, 1990; Soldz et al., 1993) did not specifically screen for comorbid OCD, which is a limitation of their methodology. To fully understand interpersonal functioning in OCPD, this study separately recruited individuals diagnosed with OCPD (without OCD) as well as those with comorbid OCPD and OCD.

THIS STUDY

This study was the first to systematically assess interpersonal functioning in OCPD, with and without comorbid OCD. Based on previous research investigating interpersonal functioning in OCPD, this study had three main aims. First, we wanted to explore the specific types of interpersonal problems associated with OCPD. Based on the findings of Cain (2011) and Villemarette-Pittman et al. (2004), we hypothesized that patients with OCPD would report interpersonal problems that were hostile, dominant, and controlling. Second, we wanted to investigate the types of interpersonal sensitivities associated with OCPD. Given the predicted interpersonal hostility and coldness associated with OCPD, we hypothesized that OCPD patients would report interpersonal sensitivity to warm interpersonal behavior by others. Finally, we predicted that individuals with OCPD would score higher on the systemizing mechanism and lower on empathy than healthy controls.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were adult outpatients (ages 18–60) who presented to the Center for OCD and Related Disorders at the New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University. They were recruited by advertisements, the program’s website, clinician referral, and word of mouth. Eligible participants had no significant medical problems and no current or past neurological disorder. Participants were excluded for prominent suicidal ideation, drug or alcohol abuse in the last 6 months, lifetime mania, psychosis, and substance dependence, and if they declined participation. A total of 150 individuals were screened for OCPD with and without comorbid OCD and 50 individuals were screened for inclusion in the healthy control group. A final sample of 75 volunteers participated, grouped by principal diagnosis: (a) 25 individuals with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM–IV–TR]; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) OCPD diagnosis and no history of OCD, (b) 25 individuals with DSM–IV diagnoses of both OCPD and OCD with clinically significant symptoms (as defined by Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale [YBOCS; Goodman et al., 1989] total score ! 16; interrater reliability for the YBOCS was > .90), and (c) 25 healthy control subjects (HC) with no current or lifetime DSM–IV Axis I or II diagnoses, and no exposure to psychotropic medications. HC participants were recruited who matched the other groups on age, sex, race, and years of education; none reported a history of OCD or OCPD in first-degree relatives as assessed by the Family History Screen (Weissman et al., 2000).

In the OCPD group, 13 (52%) participants reported no current Axis I diagnosis, and 12 subjects endorsed a cooccurring anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia). OCPD was the only Axis II diagnosis for 18 (72%) participants in this group, and 7 (28%) participants also met criteria for avoidant personality disorder. In the OCPDCOCD group, OCD was the only current Axis I diagnosis for 22 (88%) individuals, and 3 participants had a cooccurring anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia). OCPD was the only Axis II diagnosis for 23 (92%) OCPD+OCD participants, and 2 participants also met criteria for avoidant personality disorder.

Procedures

The institutional review board approved the study and participants provided written informed consent before testing. All study procedures occurred on one day.

After a phone screening, individuals interested in the study received an in-person intake clinical interview by a senior clinician (MD or PhD). Independent evaluators (PhD-level clinical researchers with extensive experience in OCPD and OCD) then conducted structured diagnostic interviews. Psychiatric and personality disorder diagnoses were confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders– Patient version (SCID–I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, &Williams, 1996) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID–II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) respectively. OCPD severity was operationalized as the total number of DSM–IV OCPD symptoms coded as present and clinically significant on the SCID– II. If discrepancies occurred between the intake clinical interview and the structured diagnostic interviews, they were discussed and a consensus diagnosis was reached. All evaluators completed extensive training on the SCID–I/P and SCID–II (e.g., observing at least three live interviews conducted by a senior interviewer and conducting three or more interviews with a senior interviewer present). Trainee and senior interviewers derive diagnoses independently. Before serving as a diagnostic interviewer in this study, the trainee had to agree with the senior interviewer on three consecutive interviews on the principal diagnosis and on the presence of all additional current and lifetime diagnoses, thus demonstrating high inter-rater reliability with senior interviewers.

Measures

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Circumplex Scales. The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Circumplex Scales (IIP–C; Alden et al., 1990) is a 64-item measure that contains items describing a range of interpersonal behavior related to “It is hard for me to ...” and “Things I do too much.” The IIP–C assesses interpersonal problems across eight themes emerging around the dimensions of dominance and warmth: domineering, vindictive, cold, socially avoidant, nonassertive, exploitable, overly warm, and intrusive (see Figure 1). Respondents are asked to indicate their degree of distress associated with the problem on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The alpha coefficients in this sample ranged from .75 for the vindictive scale to .94 for the nonassertive scale, which is consistent with previous research (Alden et al., 1990).

Interpersonal Sensitivities Circumplex. The Interpersonal Sensitivities Circumplex (ISC; Hopwood et al., 2011) is a 64-item measure that contains items describing a range of interpersonal behaviors enacted by others that might bother a respondent across eight themes emerging around the dimensions of dominance and warmth: sensitive to control, sensitive to antagonism, sensitive to remoteness, sensitive to timidity, sensitive to passivity, sensitive to dependence, sensitive to affection, and sensitive to attention seeking (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. - An example of a circumplex structural summary.

Note. X axis = circumplex angle in degrees; Y axis = standard (z) score on interpersonal circumplex (IPC) octant; Angular displacement = the person’s interpersonal “central tendency,” signifying the individual’s “typology” (Leary, 1957). Amplitude = measure of profile differentiation. It is viewed as a measure of the profile’s “structured patterning,” or degree of differentiation, indicating the extent to which the predominant trend “stands out.” High amplitude values indicate a profile with a single, distinct interpersonal peak (and trough) and low amplitude values indicate an undifferentiated profile. Elevation = an index of interpersonal distress or general interpersonal sensitivity.

Respondents are asked to indicate their general interpersonal sensitivity when another person engages in the item’s behavior on an 8-point scale ranging from 0 (never, not at all) to 7 (extremely, always bothers me). The alpha coefficients in this sample ranged from .75 for the sensitive to affection scale to .91 for the sensitive to passivity scale, which is consistent with previous research (Hopwood et al., 2011).

Interpersonal Reactivity Index. The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1980) is a 28-item self-report measure that consists of four 7-item subscales, each of which assesses a different aspect of empathy: perspective taking (the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological point of view of others), fantasy (the tendency for individuals to transpose themselves imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictitious characters in books, movies, or plays), empathic concern (other-oriented feelings of sympathy and concern for unfortunate others), and personal distress (self-oriented feelings of personal anxiety and unease in tense interpersonal settings). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (does not describe me well) to 4 (describes me very well). The subscales of the IRI have been shown to have high test–retest reliability and internal consistency. The IRI has not previously been used with OCPD individuals, although it has been used with OCD individuals (Fontenelle et al., 2009). The alpha coefficients in this sample ranged from .76 for the perspective taking and personal distress subscales to .86 for the fantasy subscale, which is consistent with previous research (Davis, 1980, 1983).

Systemizing Quotient Scale–Short. The Systemizing Quotient Scale–Short (SQ–Short; Wakabayashi et al., 2006) is a 25-item self-report measure designed to assess the drive to analyze variables in a system as well as the drive to derive the underlying rules that govern the behavior of that system. It was developed to be a shorter version of the 60-item Systemizing Quotient Scale (Baron-Cohen et al., 2003). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Example items include “I am fascinated by how machines work,” “In math, I am intrigued by rules and patterns governing the numbers,” and “When I look at a mountain, I think about how precisely it was formed.” This measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity and has been used with clinical samples, such as those with autism and individuals with obsessive–compulsive symptoms (Abramson et al., 2005). This is the first study to use the SQ– Short in individuals with OCPD. The alpha coefficient in this sample was .88.

Statistical Analysis

To investigate the types of interpersonal problems and interpersonal sensitivities associated with OCPD with and without comorbid OCD, we used the structural summary method for analyzing circumplex data (Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Wright, Pincus, Conroy, & Hilsenroth, 2009), which models an interpersonal profile of octant scores with a cosine-curve function. As Figure 2 shows, the parameters of this curve are its (a) angular displacement or the predominant interpersonal problem on the IIP or predominant interpersonal sensitivity on the ISC; (b) amplitude or a measure of interpersonal profile differentiation; and (c) elevation, an index of interpersonal distress across all types of interpersonal problems on the IIP or an index of general interpersonal sensitivity across all types of interpersonal behaviors enacted by others on the ISC, with high values (>1) indicating high overall distress and general sensitivity. The goodness-of-fit of the modeled curve to actual scores can be evaluated by calculating an R² value, which quantifies the degree to which the interpersonal profile conforms to prototypical circumplex expectations (i.e., a perfect cosine curve with an R² value of 1.00; see Figure 2). To the extent that a group’s interpersonal profile exhibits nontrivial amplitude (i.e., is differentiated) and conforms well to circumplex expectations (i.e., R² ! .70), the group might be distinctively characterized by the prototypical interpersonal pattern indicated by the profile’s angular displacement. Detailed descriptions of the structural summary, procedures for solving for the various parameters, and interpretive guidelines that relate each of these summary features to clinical hypotheses have been reported (Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Wright et al., 2009).

Following the methods and guidelines recommended by Wright et al. (2009), circular means, circular variances, and 95% circular confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated for each group on the IIP and ISC. The circular mean represents the average of the angular displacements for each individual within the group. The angle as defined by a circular mean will differ slightly from the angular displacement given by the structural summary method. The reason is that circular means are calculated using only angular location, not taking into account profile differentiation, thus all angles are afforded equal weight in the equation. The circular variance refers to the dispersion of the angular displacements of individuals within a given group around the circular mean. Circular CIs are calculated as a way of identifying reliable differences in groups’ circular means, allowing for a direct statistical comparison between groups, with the expectation that CIs will not overlap.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared across groups (OCPD, OCPD+OCD, HC) using analyses of variance for continuous variables (e.g., age and OCPD severity) and chi-square analyses for categorical variables (e.g., gender, ethnicity, marital status, employment status, highest level of education attained, lifetime mental health treatment, lifetime psychiatric medication use). Because previous research has demonstrated gender differences in systemizing and empathizing (Baron-Cohen, 2006; Baron-Cohen et al., 2003; Wakabayashi et al., 2006), gender was a covariate in analyses investigating group differences on the IRI and SQ– Short. A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses (p < .05) was conducted to investigate group differences on the subscales of the IRI while controlling for gender. Finally, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc analyses (p < .05) was conducted to examine group differences while controlling for gender on the SQ–Short.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the three groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences among the three groups on age, gender, race, marital status, employment status, and highest level of education. As expected, there were significant differences among the three groups on clinical characteristics. Individuals with OCPD, with and without OCD, scored higher on OCPD severity as compared to HC individuals.

Interpersonal Profiles on the IIP and ISC

Using the structural summary method, an interpersonal profile was calculated for each group on the IIP and the ISC (Table 2). On the IIP, the OCPD group reported hostile dominant interpersonal problems and high interpersonal distress, whereas the OCPD+OCD group reported nonassertive interpersonal problems and high interpersonal distress. Both groups exhibited prototypical circumplex profiles on the IIP (all R² values > .70) and amplitude values for both groups showed good profile differentiation. These results support assertions that there are distinct interpersonal profiles associated with each group. As expected, the HC group did not report a distinct interpersonal profile on the IIP as evidenced by their nonconformity to circumplex expectations and low profile differentiation (R² = .32; amplitude = 0.06). Figure 1 depicts the predominant interpersonal problem reported by the OCPD and OCPD+OCD groups.

On the ISC, the OCPD group reported being sensitive to interpersonally warm dominant (extraverted) behavior in others along with high levels of general interpersonal sensitivity, whereas the OCPD+OCD group reported being sensitive to interpersonally warm submissive (agreeable) behavior in others, also with high levels of general interpersonal sensitivity. Again, both groups exhibited prototypical circumplex profiles on the ISC (all R² values > .70) and amplitude values for both groups showed good profile differentiation. These findings also support the assertion that distinct types of sensitivities characterize the groups. As expected, the HC group did not report a distinct interpersonal profile on the ISC as evidenced by their nonconformity to circumplex expectations and low profile differentiation (R² = .36; amplitude = 0.05). Figure 3 depicts the predominant interpersonal sensitivity reported by OCPD and OCPD+OCD groups.

As an alternative to the structural summary method, circular means, circular variances, and 95% CIs were also calculated for each group on the IIP and ISC (see Table 2). The structural summary method models circumplex data as an interpersonal profile using a cosine curve function, whereas circular statistics allow for direct between-group statistical comparisons of circumplex data. Notably, the CIs of the OCPD and OCPD+OCD groups do not overlap on the IIP or on the ISC, bolstering evidence that individuals within each of these clinical groups are reporting distinct interpersonal profiles.

TABLE 1. - Demographic and clinical characteristics of obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), OCPD + OCD, and healthy controls (HC).

Note. Results by group are presented as mean (SD) for analysis of variance and number (percentage) for chi-square. Different alphabetical superscripts indicate significant differences in post-hoc Bonferroni analyses. OCPD severity = number of clinically significant DSM–IV OCPD criteria met (out of eight).

TABLE 2. - Interpersonal profiles on the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP) and Interpersonal Sensitivities Circumplex (ISC).

Note. OCPD = obsessive–compulsive personality disorder; OCD = obsessive–compulsive disorder; HC = healthy controls; Angle = circumplex location of the predominant interpersonal problem on the IIP and predominant interpersonal sensitivity on the ISC in degrees; Elevation = interpersonal distress on the IIP and general interpersonal sensitivity on the ISC; Amplitude = a measure of profile differentiation on IIP and ISC; R² = interpersonal prototypicality on IIP and ISC; Circular mean = the average of the angular displacements for each individual within the group on the IIP and ISC; Circular variance = the dispersion of the angular displacements of individuals within a group around the circular mean on the IIP and ISC; 95% circular CIs = 95% circular confidence intervals that identify reliable differences in circular means on the IIP and ISC.

Comparisons on Empathy and Systemizing Between Groups

We then compared the three groups on the subscales of the IRI to investigate differences in perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress while controlling for gender (Table 3). The results of the MANCOVA were significant, F(8, 136) = 6.83, p < .001, n² = 0.29. Follow-up univariate analyses with Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated that the OCPD group and OCPD+OCD group reported lower levels of perspective taking (M = 12.64 and M = 14.72, respectively) as compared to the HC group (M = 19.32), with an effect size of 0.35. In addition, the OCPD group reported higher levels of fantasy (M = 15.96) as compared to the HC group (M = 11.28), with an effect size of 0.09. The OCPD group and the OCPD+OCD group also reported higher personal distress (M = 10.92 and M = 9.96, respectively) as compared to the HC group (M = 6.40), with an effect size of 0.14. There were no significant differences among the three groups on empathic concern.

Finally, we investigated group differences in level of systemizing (SQ–Short). The results of the ANCOVA indicated that there were no significant differences among the three groups on the SQ–Short while controlling for gender, F(2, 71) = 0.44, p = .643, n² = 0.01. We then explored gender differences on the SQ–Short within each group. There were significant differences between men and women in the OCPD group, F(1, 23) = 9.33, p = .006, n² = 0.29, with men reporting higher levels of systemizing (M = 27.56) than women (M = 18.06). There were no significant gender differences in the OCPD+OCD group, F(1, 23) = 1.56, p = .224, n² = 0.06, or in the HC group, F(1, 23) = 0.10, p = .753, n² = 0.01, on the SQ–Short.

TABLE 3. - Mean comparisons on the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) while controlling for gender.

Note. OCPD = obsessive–compulsive personality disorder; OCD = obsessive–compulsive disorder; HC = healthy controls; IRI = Interpersonal Reactivity Index; n² = measure of effect size in analysis of covariance. Different alphabetical superscripts indicate significant differences in post-hoc analyses.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

This study represents an important first step in understanding interpersonal functioning in OCPD by systematically examining measures of interpersonal problems, interpersonal sensitivities, empathy, and systemizing in a clinical sample with a principal diagnosis of OCPD, with and without comorbid OCD. First, we found that individuals with OCPD reported hostile dominant interpersonal problems and high interpersonal distress. Previous research on OCPD using the IPC has been mixed, with some researchers reporting that OCPD is not associated with a predominant interpersonal problem (Pincus & Wiggins, 1990), some researchers reporting that OCPD is associated with nonassertive interpersonal problems (Matano & Locke, 1995; Soldz et al., 1993), and more recent research showing that OCPD is associated with hostile dominant interpersonal problems (Cain, 2011). However, as noted earlier, OCPD was not the principal diagnosis in these mixed samples, which might be one reason for the discrepant findings. In addition, none of these studies systematically screened for the presence of OCD, which has been shown to be highly comorbid with OCPD (Gordon et al., 2013; Starcevic et al., 2013) and interpersonally heterogeneous (Przeworski & Cain, 2012). To address these limitations, this study recruited clinical samples of OCPD (without OCD) as well as OCPD with comorbid OCD to fully explore interpersonal functioning in OCPD. Our finding that individuals with OCPD report hostile dominant interpersonal problems is consistent with the research of Cain (2011), as well as previous research linking the core features of OCPD, such as perfectionism and rigidity, to interpersonal aggression (Ansell et al., 2010; Ansell, Pinto, Edelen, & Grilo, 2008; Hummelen et al., 2008; Villemarette-Pittman et al., 2004).

FIGURE 3. - An example of the interpersonal sensitivities circumplex and the interpersonal sensitivities reported by the obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and OCPD + obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) groups.

Note. Octants are labeled with the alphabetical notation originally provided by Leary (1957; e.g., PA, BC, DE, etc.). OCPD group (n = 25) located at 32.66° with an amplitude value of 0.74, and OCPD+OCD group (n = 25) located at 313.49° with an amplitude value of 0.98. All angular locations are approximate. The distance from the center of the circle indicates vector length, or an index of profile differentiation (e.g., closer to the center of the circle indicates lower profile differentiation, farther from the center indicates higher profile differentiation).

OCPD individuals in this study reported being overly controlling, vindictive, and cold in their interpersonal relationships.

In contrast, individuals with OCPD+OCD reported nonassertive interpersonal problems and high interpersonal distress. Previous research has shown that disorders with marked anxiety, such as OCD, are generally associated with more avoidant, nonassertive, and exploitable interpersonal problems (e.g., Cain, Pincus, & Grosse Holtforth, 2010; Przeworski et al., 2011). In addition, recent research by Przeworski and Cain (2012) showed that OCD individuals report interpersonal problems with being nonassertive, exploitable, and intrusive. Our results highlight the importance of a multifaceted diagnostic assessment at the start of treatment to fully assess OCPD with and without comorbid OCD.

Second, consistent with the research of Hopwood et al. (2011), we found that OCPD individuals reported sensitivity to interpersonally warm-dominant behavior in others. These individuals report being controlling and cold in their interpersonal relationships and are sensitive to individuals who are enacting controlling, but warm interpersonal behavior. Interestingly, individuals with OCPD+OCD are interpersonally sensitive to warm submissive behavior by others. Our results suggest that interpersonal warmth in particular is an interpersonal irritant for individuals with OCPD, with or without comorbid OCD (Henderson & Horowitz, 2006). It might be that warmth in others could frustrate the interpersonal motives of OCPD individuals, which involve being more emotionally restrained, rigid, and in control in relationships (Hummelen et al., 2008; Pinto et al., 2008).

On a measure of empathy (the IRI), individuals with OCPD, with and without comorbid OCD, reported low levels of perspective taking as compared to healthy controls. Perspective taking is the ability to spontaneously adopt the psychological viewpoint of others. OCPD individuals report difficulties with being able to see things from another’s point of view, consistent with previous research associating OCPD with rigidity and stubbornness (Hummelen et al., 2008; Pinto et al., 2008). In contrast, we found no differences between OCPD individuals, with and without OCD, and healthy controls on the empathic concern subscale. Empathic concern involves sympathy and concern for the unfortunate circumstances of others, a more affective component of empathy (Davis, 1983). Our findings suggest that individuals with OCPD might have the capacity to experience sympathy and concern for others and might be able to intuit the appropriate affective response to another person, similar to healthy controls, but are limited in their ability to subsequently demonstrate the appropriate emotional response in a social situation or adopt the other person’s point of view.

In addition, we found that individuals with OCPD, with and without OCD, also reported high levels of personal distress as compared to healthy controls. Personal distress on the IRI measures a more self-oriented aspect of empathy, feelings of personal anxiety and unease in tense, difficult interpersonal relationships. This is consistent with our findings using the IPC that individuals with OCPD, with and without OCD, report high interpersonal distress and high general interpersonal sensitivity. Interestingly, individuals with pure OCPD reported higher levels of fantasy on the IRI, which involves the tendency to transpose themselves imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictional characters. The fantasy subscale of the IRI encompasses cognitive empathy, which is considered to be a more intellectualized reaction to others rather than an emotional reaction (Davis, 1983), thus it is likely that OCPD individuals use a more cognitive, intellectualized style to cope with interpersonal situations by escaping into fantasy rather than taking another’s perspective (McWilliams, 2011).

Our findings showing that OCPD individuals report an interpersonal profile that is controlling, hostile, sensitive to interpersonally warm behavior by others, and low on perspective taking is consistent with the research on systemizing. In fact, Hummelen et al. (2008) suggested that individuals with OCPD have an inborn tendency toward systemizing, which leads to the development of stubbornness, rigidity, and perfectionism. However, contrary to our expectations, individuals with OCPD, with and without comorbid OCD, did not report more systemizing than healthy controls. We did find that men in the OCPD group reported more systemizing than women in the OCPD group, which is line with previous research showing higher rates of systematizing in males (Baron-Cohen et al., 2003). One possible explanation for our findings might be that the interpersonal control and dominance associated with OCPD could manifest in different ways in males and females. In OCPD males, interpersonal control might be more related to deriving rules, analyzing, and making predictions about another’s behavior, which is consistent with increased systemizing. As this is the first study to assess systemizing in OCPD, further research is needed on this interpersonal dimension.

Clinical Implications

Despite evidence showing individuals diagnosed with OCPD frequently seek individual psychotherapy (Bender et al., 2001), there are currently no empirically supported treatments for OCPD. This study suggests that targeting the interpersonal profile associated with OCPD might offer a useful avenue for developing treatment interventions for this clinical population. In particular, we found that individuals with OCPD report hostile dominant interpersonal problems. This is consistent with previous research investigating the interpersonal style associated with maladaptive perfectionism, a hallmark symptom of OCPD. Slaney, Pincus, Uliaszek, and Wang (2006) found two interpersonal subtypes associated with maladaptive perfectionism: a hostile dominant group and a friendly submissive group. In the depression treatment literature, perfectionism has also been shown to impede successful treatment regardless of modality (Blatt, 1995; Blatt, Zuroff, Bondi, Sanislow, & Pilkonis, 1998) in part due to its adverse impact on the therapeutic alliance. Our current results combined with previous research suggest the importance of designing treatment interventions tailored to target the interpersonal hostility and dominance associated with OCPD, such as skills training to promote emotional awareness and relationship flexibility.

We also found that individuals with OCPD might be able to experience empathic concern for others, but lack the skills to appropriately respond to or fully understand the affective experience of another person (low perspective taking). Treatment interventions aimed at increasing perspective taking and the capacity to respond to emotion in a fluid and appropriate manner could improve treatment outcome for this population (Dimaggio et al., 2011). Similarly, in this study, individuals with OCPD seemed to report higher use of intellectualized coping strategies when faced with interpersonal situations (high fantasy on the IRI). Interventions aimed at reducing this reliance on intellectualization as a coping skill could also improve treatment outcome for OCPD individuals.

Finally, we found that OCPD individuals, with and without OCD, reported increased sensitivity to interpersonal warmth enacted by others, which could also have implications for psychotherapy. Therapists across all orientations generally attempt to work in their patients’ best interest and to promote a positive therapeutic relationship (Pincus & Cain, 2008). It is quite possible based on our results that a patient with OCPD could become frustrated, irritated, or even angry by any perception of interpersonal warmth by the therapist, which will in turn inhibit the development of the therapeutic alliance. Through a thorough understanding of interpersonal functioning in OCPD, the therapist can begin to anticipate and predict the effects of therapeutic behaviors on the OCPD patient to facilitate a working alliance and improve treatment outcome (Tracey, 2002).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study and its conclusions have several limitations. First, our sample size (n = 25 in each group) was relatively small and future research should include a larger sample size. Second, our findings might not generalize to OCPD individuals who do not respond to advertisements for research or who refuse to participate in research. Third, 28% of the OCPD group also met criteria for avoidant personality disorder. Although this is consistent with previous research (e.g., McGlashan et al., 2000), and our results suggest that the OCPD group was interpersonally cohesive (e.g., good interpersonal prototypicality on the IIP and ISC), future research should include a larger sample of OCPD patients to address issues with comorbidity. Finally, our outcome data are limited by reliance on self-report data. Future studies should include informant ratings (e.g., peers, significant others, family members) of interpersonal functioning in OCPD to better elucidate the impact of these specific interpersonal styles on the OCPD individual’s interpersonal context.

In conclusion, this study provided the necessary first step toward clarifying interpersonal functioning in OCPD. We found that OCPD individuals reported hostile-dominant interpersonal problems and sensitivities with warm-dominant behavior by others, whereas OCPD+OCD individuals reported submissive interpersonal problems and sensitivities with warm-submissive behavior by others. Individuals with OCPD, with and without OCD, reported less perspective taking and more personal distress than healthy controls. Finally, we found that OCPD males reported higher systemizing levels than OCPD females, indicating that interpersonal control might manifest differently in OCPD males. Overall, our results suggest that interpersonal deficits are an important feature of OCPD pathology, consistent with the greater emphasis on interpersonal dysfunction in the DSM–5 proposed model for personality disorders (included in Section 3 of the DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Finally, this study points to new treatment directions for OCPD. Interventions tailored to target the interpersonal profile of OCPD could be beneficial, such as skills-based approaches to increase perspective taking and the capacity for understanding and responding to emotion.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) grant K23 MH080221 to Anthony Pinto.

References available in original article on Journal of Personality Assessment.