Good Psychiatric Management for Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Disorder

Originally published by: SpringerLink

Written by: Ellen F. Finch, Lois W. Choi‐Kain, Evan A. Iliakis, Jane L. Eisen, Anthony Pinto

Purpose of Review Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is a prevalent personality disorder that frequently presents in health care settings with other psychiatric comorbidities. However, no OCPD treatment guidelines for a general mental health clinician have been proposed.

This review summarizes current, clinically relevant knowledge about OCPD and introduces a pragmatic and accessible treatment model: Good Psychiatric Management (GPM) for OCPD.

Recent Findings GPM for OCPD offers clinicians a straightforward frame work for understanding and treating OCPD patients, informed by eight principles: (1) diagnostic disclosure with assessment of the effect of perfectionism and rigidity on occupational and social life, (2) psychoeducation regarding the role of over-reliance on overcontrol as a core mechanism of instability, (3) focus on life outside of treatment as a grounds for personal growth, (4) use of corrective experiences to dispel rigidly held beliefs and promote more flexible personality functioning, (5) managing comorbidities, (6) use of multimodal treatments, (7) managing safety using general suicide risk assessment, and (8) conservative pharmacological management.

Summary Guided by up-to-date knowledge about OCPD, an accessible OCPD conceptualization, and GPM’s eight principles, the generalist mental health clinician can help their patient to build a meaningful life beyond OCPD symptoms.

Introduction

Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is the most prevalent personality disorder in the western world. Despite its high level of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, moderate levels of psychosocial impairment, high economic costs, and reduced quality of life, no evidence-based treatments have been tested in randomized controlled trials. This article provides an overview of the current state of knowledge about OCPD and introduces an adaptation of Good Psychiatric Management (GPM), a generalist clinical management framework informed by what we know from existing research on OCPD.

Understanding OCPD

OCPD is characterized by a pervasive orderliness, perfectionism, and a preoccupation with control in mental and interpersonal domains at the expense of flexibility and efficiency. Those with OCPD act with rigidity, stubbornness, and intense emotional restraint that causes significant impairment, particularly in interpersonal contexts. These symptoms are ego-syntonic to the individual with OCPD. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for OCPD list eight items that include both rigid, ritualized behaviors (e.g., orderly placement of items, excessive list making) and trait-like personality features (e.g., perfectionism). This diagnostic framework has relatively poor psychometric properties, as well as limited specificity and sensitivity. The Alternative Model of Personality Disorders (AMPD) proposes a more focused set of diagnostic criteria for OCPD, simply requiring the trait of rigid perfectionism as a central feature of OCPD. In line with the field’s shift towards dimensional model for personality disorders, the AMPD focuses on trait-based assessment; therefore, it removes the specific behavioral criteria of miserliness and hoarding. Instead, it centralizes core features of perfectionism and rigidity, with an emphasis on how these traits impact broader functionally relevant criteria, such as intimacy avoidance and perseveration.

To categorize subtypes within OCPD, Pinto delineates the controlling and anxious presentation styles. Individuals who present with the controlling style tend to have difficulty with emotion regulation and feel chronically frustrated by the insufficiency of others. They are more likely to be verbally hostile when others fail to meet their perfectionistic standards, tending towards controlling behaviors and judgmental attitudes in their interpersonal relationships. In contrast, individuals who present with the anxious style tend to be prone to worry and emotional avoidance. For those who present with the anxious style, perfectionistic standards result in scathing self-criticism and over attention to the expectations of others. Those with the anxious style tend to be more submissive and avoidant of intimacy altogether.

Prevalence estimates of OCPD in community samples vary from 1% to 8%, making OCPD the most prevalent personality disorder in the general population. However, when only including those whose symptoms cause them significant distress, the 8% prevalence rate drops to 1.9%, suggesting that approximately one in four individuals meeting symptomatic threshold for OCPD does not perceive themselves as meaningfully impaired. OCPD is associated with better global functioning than other personality disorders. Those with OCPD tend to instead experience impairment concentrated in a single domain, most commonly interpersonal relationships or global satisfaction. Still, those living with OCPD have worsened quality of life and moderate psychosocial impairment. Despite its association with relatively good functioning, OCPD remains costly to patients with the diagnosis as well as society. In a national Dutch study on the economic burden of personality disorders, OCPD and borderline personality disorder (BPD), as compared to other personality disorders, were significantly associated with increased mean total costs, including direct medical costs and indirect costs due to lost productivity. This finding is striking given the availability of evidence-based BPD treatments in contrast to the absence of any well-delineated treatment guidelines for OCPD.

The literature regarding the etiology and course of OCPD is relatively sparse. OCPD is understood as modestly heritable, with genetics explaining approximately 27% of the variance in OCPD. Specific environmental factors have been shown to influence the development of OCPD above and beyond genetics. These factors are theorized to include parental overcontrol, learned compulsive behavior, and reinforced hyper-responsibility. More recently, neurocognitive functioning has been examined in those with OCPD. Studies suggest that OCPD traits may in part result from executive control deficits, with rigid rules and systems compensating for cognitive disorganization, an excessive capacity to delay reward, and excessive cognitive control and inflexibility.

Multiple studies demonstrate relatively high rates of remission from OCPD within 1 to 2 years; however, the persistence of OCPD’s core features suggests a more chronic course. Cross-sectional studies find high point prevalence rates of OCPD (17.1%) in geriatric populations, indicating that OCPD might actually worsen over time or manifest later in life. Discrete behavioral symptoms may remit with relative ease, whereas trait-like symptoms appear more resistant to change. In a study of individuals with OCPD, McGlashan and colleagues found that the trait-like symptoms of rigidity and problems delegating remained fairly constant over the course of 2 years, whereas behavioral criteria of miserliness and strict moral behaviors were more likely to improve.

Detailed in Table 1, OCPD has relatively high rates of psychiatric comorbidity with other disorders of overcontrol including OCD (20–32%) and eating disorders (20–61%), as well as anxiety disorders including panic disorder (5–11%), generalized anxiety disorder (16%), and social phobia (21%). Further, those with OCPD demonstrate high rates of comorbid substance use disorder (58%) and mood disorders (31%). These co-occurring disorders drive the relatively high rate of treatment utilization seen in individuals with OCPD, most frequently in individual outpatient psychotherapy or primary care settings. Thus, although mental health professionals may not frequently see patients presenting for help with their ego-syntonic OCPD symptoms, they are likely to find their clinical management of other co-occurring disorders complicated by OCPD traits, which will require attention for optimal treatment response.

Table 1. Comorbidity of OCPD with other psychiatric diagnoses (lifetime prevalence unless otherwise specified)

a. Time frame for all diagnoses unspecified.

b. Both diagnoses current.

c. Time frame for diagnosis in row: current; OCPD time frame unspecified

N/A, not available

Despite the likelihood that most mental health professionals will encounter patients with OCPD or OCPD traits in their routine clinical practice, there is limited empirical literature on OCPD treatment. There are a handful of studies of psychotherapy for OCPD (e.g.,; for review, although they are mostly uncontrolled trials and case studies. Early clinical literature points towards psychodynamic treatments (e.g.,), which aims to increase patient’s insight into how OCPD traits are employed to defend against feelings of insecurity and uncertainty. Multiple uncontrolled treatment trials (e.g.,) suggest that cognitive therapeutic approaches, which operate through identifying and restructuring maladaptive thoughts, may be effective. Radically open dialectical behavior therapy (RO-DBT), a promising and comprehensive transdiagnostic treatment specified for disorders of overcontrol, including OCPD, has been manualized. However, no randomized controlled trials have yet established RO-DBT’s efficacy for OCPD, and its highly specialized and intensive format limits its dissemination. Pinto described a more scalable 14-session intervention for OCPD that combines modules from two well-established cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) protocols: CBT for clinical perfectionism and rigidity and Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR). By using the DBT-based STAIR protocol to enhance skills for emotional regulation and interpersonal skillfulness prior to exposures related to perfectionism and rigidity, Pinto’s approach stabilizes the general personality dysfunction that often impedes the establishment of a durable therapeutic alliance prior to attending to the core traits of OCPD.

Although therapies for OCPD have garnered modest support and specified tailoring of treatments for OCPD is emerging, there are few guidelines for the generalist practitioner treating patients with OCPD. Given its prevalence, mental health clinicians need a time-efficient intervention to help patients with their OCPD symptoms without needing to provide highly specialized therapies. General or good psychiatric management (GPM) provides a distillation of clinical knowledge for treating individuals with OCPD that can be easily learned and applied in a variety of clinical settings as well as integrated with treatments for other disorders.

Good Psychiatric Management (GPM)

Good Psychiatric Management (GPM) is a pragmatic and principle-driven clinical management approach for borderline personality disorder (BPD). Instead of relying on complex psychotherapeutic techniques or theories, GPM encourages clinicians to rely on what they already know and encourages adaptation of their usual clinical case-management techniques. GPM relies on common principles of change across psychotherapeutic orientations which can guide clinicians without relying on specified psychotherapeutic techniques or procedures.

GPM was developed from the American Psychiatric Association Guidelines and Gunderson’s clinical guide to BPD and manualized by Paul Links for use in one of the largest most methodologically rigorous randomized control trials for outpatient psychotherapy for BPD to date. This trial showed no statistically significant differences in all major outcomes between GPM and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), a more time and training intensive treatment, at both the end of 12 months of treatment and 2 years later. Gunderson collaborated with Links to publish an improved version of the trial’s manualization of GPM for public consumption after the results of this trial.

Because of GPM’s demonstrated efficacy for BPD and designation as a generalist common factors approach, it has been adapted for other personality disorders, patient populations, and treatment settings. This manuscript proposes GPM’s adaption for OCPD. Importantly, this adaptation has not been empirically tested in patients with OCPD and thus is not considered an evidence-based treatment. Rather, it combines empirically supported GPM principles with clinical knowledge of OCPD to present a model that can guide mental health professionals treating OCPD in the absence of an evidence-based approach.

We present, first, an accessible conceptualization and model of OCPD and, second, eight GPM fundamentals for treating OCPD. These fundamentals are not meant to replace specialized approaches such as the CBT protocol developed by Pinto, but instead provide a framework to assist mental health professionals in effectively navigating treating patients with OCPD or OCPD traits in the absence of available care, or as a first step prior to more specialized psychotherapy. GPM for OCPD can also be pragmatically incorporated with treatments of comorbid disorders that are hindered by the patient’s OCPD symptoms. Ultimately, the goal of GPM for OCPD is not to eliminate all OCPD symptoms and traits, but instead to help the patient build a meaningful life through gaining adequate flexibility and a tolerance of imperfection.

GPM’s Conceptualization of OCPD

Central to GPM is a coherent model of the disorder which serves as a foundation for a clear shared conceptualization of the problems of focus for clinical management. Supported by the existing research, GPM conceptualizes OCPD as a maladaptive personality disorder where problems of self and relationships revolve around central problems of perfectionism and rigidity. Perfectionism encapsulates internal control while rigidity entails controlling effects on others. Over-reliance on these coping strategies relates to an intolerance of the discomfort and anxiety that arises when control or satisfactory performance is not achieved.

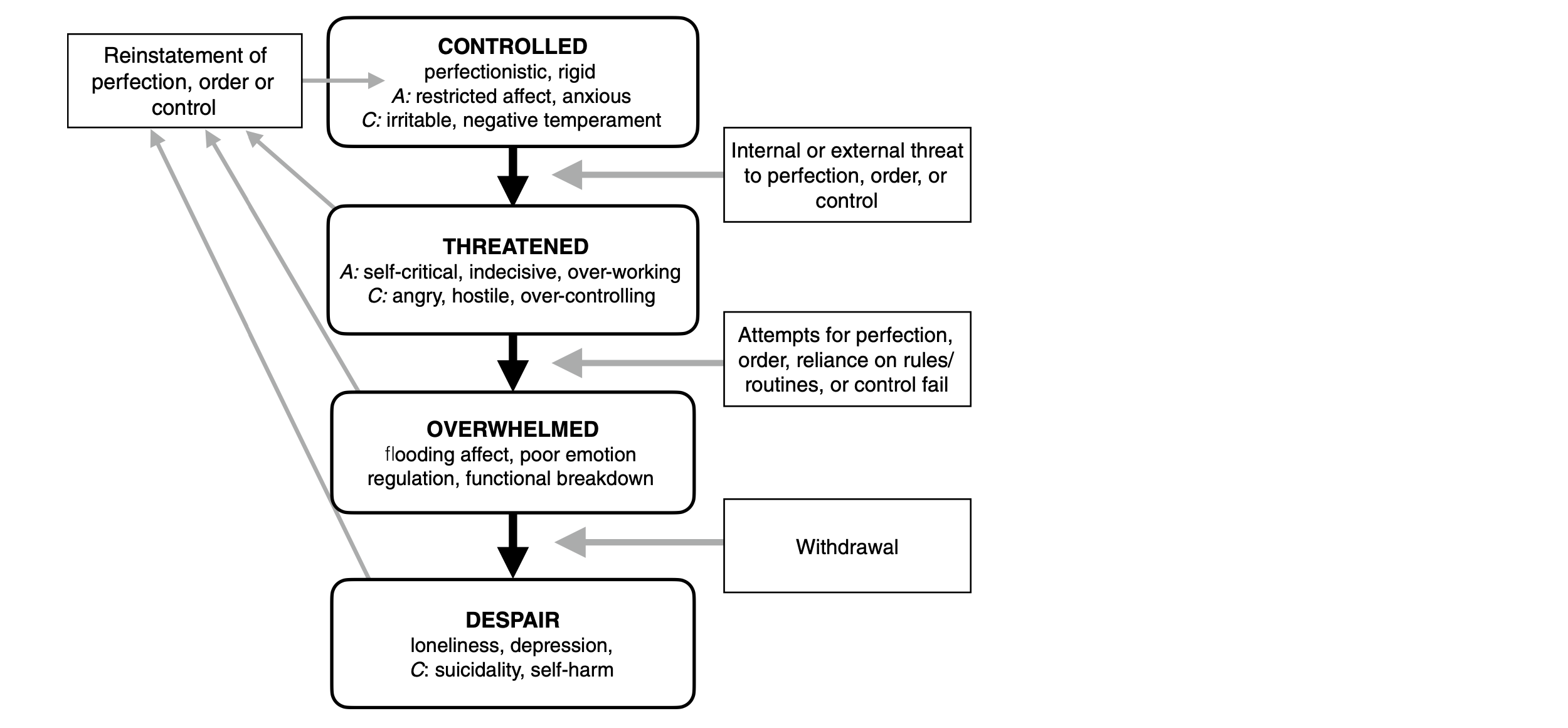

GPM integrates OCPD’s perfectionism and rigidity into a single model of OCPD pathology: the Model of Overcontrol (Fig. 1). When maintaining their own perfectionistic standards and following their rigid routines, the person with OCPD feels comfortably in control but at the same time vigilant about losing control. It is in this state that those with OCPD can find vocational success at the cost of living with restricted affect, anxiety, or irritability. However, because of the degree of dependency on control and inflexibility that hampers more adaptive coping, those with OCPD are easily threatened and destabilized. In the face of real or perceived threats to orderliness and/ or perfection, those with OCPD may oscillate to a more rigid and overcontrolling state, which may look like self-criticism, indecisiveness, and over-working (anxious style) and/or anger, hostility, and overcontrol of others (controlling style). In this threatened state, individuals with OCPD can undermine themselves and alienate those around them. At times, this excessive control of self and others may reinstate the order that is desired, but also often results in a loss of control when the patient is overwhelmed and burned out from their own unrelenting standards. Their failure can lead to a flooding of affect, which the person with OCPD has limited ability to regulate, resulting in a functional breakdown. In turn, they may develop despair and, in more severe cases, suicidality. Reconstitution may occur through asserting control in displaced, compensatory, and typically fragile means, leading to a cyclical pattern of artificially regaining control only to inevitably lose it again. The paradox of this cycle is that the quest for control causes more instability and overall life imbalance.

Fig. 1. Components that are more specific to the anxious and controlling presentation style types are denoted with A = anxious or C = controlling

GPM aims to break this cycle by helping the patient develop a more effective consistent personality style that is adaptive to situational demands to enhance self-control rather than dismantle it. Flexibility is valorized as an essential tool for tolerating imperfection and moments of dyscontrol, which is more adaptive towards helping patients achieve the functional level they desire. Patients are not asked to completely relinquish standards, but rather diminish their dependency on rigid perfectionistic control, to more sustainably grow their ability to apply “good enough” effort to meet demands while limiting responses driven by emotional dysregulation and interpersonal conflict. To this end, GPM for OCPD aims to install healthy skepticism of the tendency towards idealization of control and devaluation of dyscontrol. It highlights how that this split aggravates instability and hinders the patient’s ability to meet aims, including the maintenance of realistic control. Alongside this central model that explains shifts in symptoms and emotions within OCPD, we present eight fundamentals that work towards this goal of flexibility, summarized in Table 2.

GPM for OCPD Fundamentals

1. Diagnostic disclosure

Diagnosing the patient with OCPD is a critical first step. OCPD can be diagnosed by reviewing the DSM-5 criteria with the patient, with an emphasis on perfectionism and rigidity. The clinician should also consider drawing from the Pathological Obsessive–Compulsive Personality Scale (POPS), a psychometrically sound self-report assessment which offers concrete examples of how OCPD’s symptoms manifest. The GPM clinician can help the patient see how their OCPD traits can have both positive and negative effects, with healthy skepticism about whether an over-reliance on control works. This dialectical framing makes it more likely for the patient to willingly identify with OCPD traits and symptoms. Then, the clinician can collaboratively work with the patient to understand how OCPD connects to dysfunction in their lives. For example, has the patient’s interpersonal rigidity led to their losing or not seeking romantic relationships? Through a collaborative diagnostic process, the GPM clinician helps the patient understand their OCPD symptoms and how they are currently interfering in functioning, thus motivating engagement in treatment.

2. Psychoeducation

Following diagnosis, the clinician should educate the patient about their OCPD or OCPD traits. GPM emphasizes medicalizing the diagnosis, which helps to reduce stigma that frequently accompanies personality disorders, and using psychoeducation to motivate the patient to engage in treatment. In discussing OCPD’s prevalence, clinicians can convey how common OCPD’s features are as well as normalize and medicalize its broad range of impairment. When providing psychoeducation about OCPD’s etiology, psychosocial factors can be discussed in combination with some genetic contributions and neurocognitive tendencies. Psychosocial factors can include how OCPD traits may have some adaptive advantages for the patient earlier in life, and neurocognitive tendencies that the patient may relate to include executive dysfunction causing an over-reliance on rules and excessive cognitive control and capacity to delay reward. Clinicians can also tell patients the course of OCPD, emphasizing that the behavioral manifestations seem changeable over time, but core traits appear persistent. Forecasting the possibility that OCPD can become worse in later life may motivate individuals to work towards change in treatment earlier. A review of the prevalence of co-occurrence with other disorders and a discussion of OCPD’s contribution to risk of and worsened treatment response to other psychiatric difficulties help patients appreciate the need to manage their OCPD proactively. Lastly, noting that the evidence base for treatments specific to OCPD is too underdeveloped to prescribe any particular psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic approach, GPM clinicians can encourage general psychotherapy focused on problems of overcontrol, specified OCPD approaches, or GPM for OCPD.

Once this foundational knowledge about OCPD has been communicated, the GPM clinician can focus psychoeducation on helping the patient better understand their perfectionism and rigidity via the Model of Overcontrol (Fig. 1). Through generating a joint understanding of perfectionism and rigidity via the Model of Overcontrol, the clinician will create a common vocabulary and model through which the patient’s OCPD is understood.

Research regarding maladaptive perfectionism and rigidity can inform this discussion to provide a scientifically informed rationale for GPM’s formulation. Those with OCPD, due to maladaptive perfectionism, strive anxiously to maintain unrealistic standards, and depend on meeting standards to manage a positive sense of self and others. If standards are not met, either due to failure, avoidance, or procrastination, the perfectionistic individual reacts from a threatened angry position with harsh self-criticism or criticism of others. In patients with OCPD, avoidance and procrastination are two of the most common and dysfunctional manifestations of perfectionism. Patients may frequently delay school or work assignments until the last minute or avoid educational or professional opportunities that they predict will be too challenging. In this way, perfectionism actively undermines the patient’s desired outcomes, leading to a frustrating and self-perpetuating cycle of setting high standards and not achieving them.

Table 2. Good psychiatric management for obsessive–compulsive disorder fundamentals

When the person with OCPD is threatened, they increase in their rigidity, which refers to excessive control and insufficient flexibility around one’s thoughts, behaviors, and interpersonal interactions. Highly rigid individuals tend to approach each of these domains with unwarranted control and stubbornness and a black and white view of right and wrong. This increasingly rigid state that arises from a position of feeling threatened decreases adaptive responses in terms of both self-functioning related to coping and self-esteem and interpersonal functioning, leading to more explosive conflict or relational impasses. Trait rigidity has been associated with a number of negative outcomes, including poorer outcomes for depression, eating disorders, and suicide ideation and attempts. Interpersonal rigidity is associated with worse overall well-being, greater interpersonal distress, and less adaptive interpersonal responses. The GPM clinician can help their patient see that although rigidity may provide relief in the moment through reducing uncertainty or discomfort, in the long term, it leads to greater suffering and worse interpersonal relationships. This rigidity isolates the patient, so they become more unreachable, and burdened, leading to the very sense of failure and inadequacy they were working so hard to avoid. In the most severe cases, this more overwhelmed state can lead to break down, job or relationship loss, or even suicidality. Understanding these cycles of vulnerability using GPM’s overcontrol model enables clinicians and patients to have a shared framework for evaluating the effects of perfectionism and rigidity as well as to see the relationship between emotions, behaviors, cognitions, and interpersonal dynamics.

3. Getting a life

Following disclosing the diagnosis and psychoeducation, GPM prioritizes the patient taking tangible steps to build a meaningful life that is more closely aligned with the patient’s values. Feasible and short-term goals that help the patient enhance their daily functioning should be developed collaboratively, and the patient should be held accountable for following through with the goals that are set in session. Behavioral change is expected.

“Getting a life” in GPM for OCPD will likely focus on improving interpersonal relationships, adopting work styles not hindered by procrastination or other forms of maladaptive perfectionism, and developing aspects of identity that are not linked to rigid standards, including forms of leisure that have been neglected or never tried. The GPM therapist should help the patient set goals that work towards achieving change. A goal may be defining good enough standards as an alternative for missing deadlines or finishing work in predetermined time frames rather than by standards. Operationalizing this goal may emphasize leaving work by 6:00 pm in order to eat dinner with family at least twice a week, setting a bedtime, or sending emails without rereading them more than once, so that progress and corrective experiences can be evaluated. Further, the GPM therapist should encourage their patient with OCPD to develop meaningful leisure activities or hobbies outside of their typical perfectionistic pursuits. Importantly, GPM suggests that all goals be focused on the here and now. Although clinicians and patients alike may be tempted to delve into the developmental history of the patient or explore “how they came to be this way,” GPM recommends shifting from discussing the past to focusing on practical steps the patient can take to improve their life.

Patients with OCPD will be resistant to setting goals that will interfere with achieving their perfectionistic standards. Patients should understand that GPM for OCPD does not aim to replace a patient’s drive for productivity or success with passivity and mediocrity. Rather, it aims to help a patient live their life in a way that achieves these goals in an intentional, sustainable, and realistic manner.

Progress can be assessed by tracking success or failure to meet these goals. If a patient is consistently not changing their behavior to meet mutually agreed upon goals, this should serve as a signal that treatment is not working. Procrastination, avoidance, perfectionism, self-criticism, and hostility towards others are symptoms that are the focus of the work. They are both expected to arise in treatment, but also to decrease with treatment if it is working. More formal tools to assess symptom decrease, such as the POPS, can also be used, particularly at the end of treatment. However, given OCPD’s chronic nature, functional goals specific to the patient serve as a better marker of progress in the short term.

4. Corrective experiences

To facilitate the overall goal of “getting a life,” GPM for OCPD calls for emotional and behavioral corrective experiences, where previously held rigid and fearful beliefs that motivate overcontrolling behavior are tested by experiences of change. If patients see that their overall functioning improves with good enough standards, they may be more open to changing their beliefs about what will optimize their ability to achieve goals and live according to what they value most.

For patients that reflect a more “anxious style” of OCPD, emotional avoidance is likely pervasive. They may fear that any type of emotion risks losing control or humiliating themselves. The GPM therapist should model expressing affect/using emotion vocabulary and help the patient do the same within the therapeutic relationship. This will provide a corrective experience for the patient—they can learn that the result of expressing affect is not always harmful, and in fact can be productive, and they will gradually learn to tolerate previously aversive affective states.

For patients that reflect the “controlling style” of OCPD, affect is characterized by chronic feelings of frustration and anger, as well as broad emotion regulation difficulties. Corrective emotional experience for these patients will require a greater emphasis on emotional awareness and emotion regulation techniques, such as distress tolerance skills. Through gaining a better understanding of and control over their emotions, the patient will be better equipped to engage in change-oriented behaviors that are distressing or frustrating.

Corrective experiences should also come in the form of trying new, more realistic responses aimed to increase flexibility around daily behaviors governed by all-or-nothing thinking. GPM encourages a generic process of helping patients evaluate if their beliefs and behaviors serve their needs, goals, and interests. The patient and clinician should collaboratively set a goal of breaking a “rule” and then assess the impact of acting against rigidly held beliefs together. If the feared outcome does not occur (or even if it does occur and then life goes on), the patient learns that flexibility is not intolerable and may be adaptive to the bigger picture of the patient’s overall life. This process of encouraging corrective experiences provides the patient agency to challenge their own rigid thinking and foster growth through cultivating more flexible responses to specific life situations.

5. Managing comorbidities

OCPD has high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, detailed in Table 1, and individuals with OCPD frequently seek treatment for a comorbidity as opposed to OCPD itself. Further, independent of a formal OCPD diagnosis, perfectionism and rigidity complicate the treatment of and contribute to worse outcomes for concomitant disorders, including mood disorders, OCD, PTSD, and other personality disorders. Rather than prioritize treating OCPD and its traits above or below a given comorbidity, the GPM clinician should apply insights from the psychoeducation stage of GPM to continually investigate how OCPD-related features may be generating risk for comorbidities or interfering with responses to other treatments. OCPD and its traits are assumed to be interacting with and contributing to the comorbidities, rather than conceptualized as a distinct clinical entity.

6. Multimodal treatment

Group treatment may be particularly beneficial for the patient with OCPD. Feedback from a group of peers reduces the “tug of war” that is likely to occur in the therapist-client relationship. Experiencing conflict with other group members allows the patient with OCPD to see problems with their interpersonal style not easily accessed in individual psychotherapy or retrospective accounts of their own life. Group members struggling with similar issues may provide ways of communicating or thinking about their control struggles in ways that expand other members’ understanding of their own struggles. Comfort with emotional expression and needs, control issues, and interpersonal styles are all issues ripe for group intervention with OCPD patients.

GPM advises involving the family when useful regarding psychoeducation and accountability around behavioral goals. Since the problems of OCPD frequently come to bear in interpersonal relationships, involving the family to help the patient understand how their OCPD behaviors are affecting those they love may be a valuable tool. Structuring conversations between patients and their families on managing pragmatic concerns and asking family members to assist in providing accountability for the patient’s behavioral goals can facilitate problem solving and change without intensive family involvement.

7. Managing safety

Limited literature suggests that OCPD increases risk of suicide attempts. Further, expert clinical literature suggests that once suicidal, patients with OCPD may be at particularly high risk of completion because any suicide attempts are typically thoroughly planned. However, compared to other personality disorders, the risk of suicide is relatively low and OCPD was not an independent risk factor of attempting suicide over 10-year follow-up. Therefore, while managing suicidality will not be as frequently necessary when treating the patient with OCPD as it would be for other personality disorders, it is important for the GPM clinician, if suspecting suicidality, to explicitly ask the patient what their plans are for suicide and take any threats of suicide seriously. Interventions should be determined by an assessment of dangerousness and risk, based on general assessment of factors which increase risk. These include recent discharge from hospital, depression, substance use disorder, family history, and stressful life events. In other words, clinicians should use basic principles they generally employ for safety assessment of suicide in any diagnosis. They can combine this discussion with use of the Model of Overcontrol to understand how the patient’s suicidality develops related to rigidity and perfectionism, focusing on the need to clinically manage the mechanism that generates self-destructive concerns.

8. Conservative pharmacological management

There are only three published studies that investigate psychopharmacology for OCPD, none of which has a sample with OCPD as the primary diagnosis and only one of which is an RCT (for review). This limited evidence base suggests that carbamazepine and fluvoxamine may help in reducing OCPD traits and that citalopram may be helpful in individuals suffering from OCPD and depressive symptoms. Due to the lack of research, GPM does not recommend the use of medications for OCPD as the definitive treatment. The major role of medications is to manage comorbid features, typically depression and anxiety, so that the patient is stable enough to work on their OCPD symptoms in the therapy.

Conclusions

GPM for OCPD provides mental health clinicians with straightforward guidelines for effectively diagnosing and treating OCPD. These guidelines are not intended to replace more intensive treatments but instead serve as basic principles for the generalist mental health clinician. Through collaboratively diagnosing OCPD, helping the patient understand their symptoms via the Model of Overcontrol, and encouraging short-term goals and corrective experiences, the GPM therapist will help their patient increase their flexibility. Although the persistent nature of OCPD’s more trait-like symptoms suggests that a complete cure for OCPD is unlikely, nonetheless clinicians employing GPM can help their patient build a meaningful, values-based life beyond that would otherwise be limited by their symptoms of OCPD.

Case Vignette: Mrs. P.

Case Description

Mrs.P.,a45-year-oldwoman,presentedat an outpatient clinic seeking short-term, structured treatment for her anxiety and depression. A standard intake interview revealed that Mrs. P.’s presenting problems were strongly connected to OCPD traits. She reported an excessive devotion to her job, made difficult due to her extreme perfectionism-driven procrastination. Mrs. P.’s high standards for her colleagues and inability to delegate left her feeling overwhelmed and isolated at work. Further, she described intense moral rigidity that had led her to “disown” family and friends and was currently causing serious conflict in her marriage. Mrs. P.’s overwhelming feelings of frustration and anger, as well as frequent angry outbursts, informed a diagnosis of OCPD with a controlling style.

Intervention

Mrs. P. engaged in once weekly outpatient therapy for 20 weeks. In this treatment, GPM for OCPD was provided alongside standard cognitive-behavioral therapy for her co-occurring generalized anxiety disorder and depression. In the second session, the OCPD diagnosis was disclosed with a review of the POPS. Many items from the POPS scale, including my need to be perfect affects how much I get done and other people say I am argumentative, resonated strongly with the patient. Instead of resisting the diagnosis, Mrs. P. was quick to agree that her rigidity and need for control were contributing to her presenting problems. Although she commented that she found the term personality disorder a “bit extreme,” she expressed relief that the diagnosis aligned with her experience, particularly given that she had felt misdiagnosed for decades.

In the next session, psychoeducation about perfectionism, rigidity, and the Model of Overcontrol was shared with the patient. A recent stressful event from her life—completing an important report for work that required collaboration with a colleague—was mapped onto the model collaboratively. Although at first controlled, Mrs. P. immediately grew angry after her colleague sent their portion of the report that fell short of her perfectionistic standards. She quickly sent a hostile email telling her colleague she would complete the work alone to retain control. That night, Mrs. P. had a “breakdown” because she was overwhelmed by frustration and because the imperfect report was due the next day. She stayed up all night to complete the report, thereby reinstating her perfectionism but continuing her cycle of overcontrol.

The following two sessions were spent better understanding how Mrs. P.’s experience was driven by the model of overcontrol, as well as perfectionism and rigidity more broadly. By the fourth session, she agreed to work towards small goals that would increase flexibility. She was particularly motivated by the idea that increasing flexibility may also help with her anxiety and depression symptoms.

The next 10 weeks of treatment focused on setting meaningful goals to “get a life” and gradually engaging in corrective experiences. Short-term goals to “get a life” included not working during a weekend away with her husband, completing work assignments in pre-defined time periods to reduce perfectionism and procrastination, and getting coffee with an old friend even though he had failed to meet Mrs. P.’s moral standards. These short-term goals were monitored and used as markers of progress.

Corrective experiences took the form of both emotion regulation skills and behavioral experiments. Emotion regulation skills were particularly useful for Mrs. P. in moments of frustration with others, and she routinely used diaphragmatic breathing and grounding exercises at work and during difficult conversations with her husband. Mrs. P.’s behavioral experiments often focused on reducing perfectionism and control at work (e.g., setting strict time limits of preparation for a presentation or delegating tasks to “incompetent” coworkers) or rigidity in her personal life (e.g., allowing her husband to grocery shop without any input from her). The behavioral experiments were tracked formally, with the patient reporting her expectations beforehand and the outcomes the following week.

Throughout treatment, as advised by GPM, Mrs. P.’s comorbidities of anxiety and depression were treated in tandem with her OCPD. Instead of prioritizing one diagnosis over the other, Mrs. P.’s anxiety and depression symptoms were discussed in connection to her OCPD traits (e.g., rigid perfectionism leads to increased anxiety before submitting an important work assignment and low mood if her work does not meet her own standards). In fact, many of her behavioral experiments for OCPD could also be conceptualized as exposures for anxiety within a CBT framework. Final sessions were focused on treatment consolidation, and specific interventions focused on her depressive symptoms.

Outcomes

Following 20 weeks of GPM for OCPD, as well as CBT for anxiety and depression, Mrs. P. reported a marked decrease in her anxiety, depression, and OCPD symptoms. Some aspects of her OCPD, most notably moral rigidity, saw little change, however. Regardless, by the end of treatment, Mrs. P. engaged in more flexible thoughts and behaviors. In addition, she reported more productivity at work, a healthier relationship with her husband, and less daily frustration and anger. Through implementing GPM principles in tandem with standard CBT for anxiety and depression, the GPM clinician helped the patient recognize how her OCPD traits were causing problems and how to systematically work towards goals to increase flexibility.

References available in original article on SpringerLink.